Is it the Lower Atchafalaya or Bayou Teche?

A lifelong resident of Patterson is fighting a vernacular tidal wave that threatens what he said is the proper name of the river he loves and raised his family on.

Fulton “Butch” Felterman Jr., 86, said in the decades after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dammed the Lower Atchafalaya River just below where the Bayou Teche emptied into it, a new generation and recent arrivals from Patterson to Berwick began to call the stretch “Bayou Teche.”

He is leading the fight to get people to return to calling that approximately 10-mile stretch from Patterson to Berwick what it was called before the river flow was stopped.

“The name of the river was never changed after the dam was constructed in 1940 and I do not see why we should quietly let it change,” Felterman said. “People raised on the river know its real name but some of the younger generations do not.”

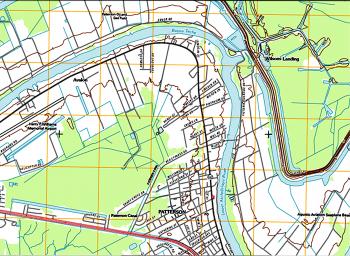

The bayou and river became a single contiguous body of water to its junction with the Atchafalaya River in the Berwick Bay after the Lower Atchafalaya River was dammed off near what became Wilson’s Landing. Yet, Felterman has a 1999 map that he said proves his point that the name did not change.

Another 2007 map provided by the corps clearly names the waterway east of Patterson, the Lower Atchafalaya River. A third map, provided by the United States Geological Survey, shows the name change occurs below the Calumet Cut near the old Indian mounds, close to what became Wilson’s Landing.

Communities outside of St. Mary Parish through which the narrow bayou traverses do not share Felterman’s commitment to map details.

The web page of the City of Breaux Bridge described the ancient Chitimacha legend detailing the birth of the river in the death of a great snake.

“Its head was at what is now known as Morgan City and its body stretched beyond ... The Bayou Teche (“Teche” meaning “snake”) is today proof of the exact position into which this enemy placed himself when overcome by the Chitimachas,” the website said of the legend.

The Evangeline Economic Development District in Lafayette prepared a document in 2000 for the Bayou Teche Scenic Byway Commission which says the Bayou Teche runs from Port Barre to Morgan City.

The Louisiana Paddle website says “the Teche begins in Port Barre ... then flows … to meet the Lower Atchafalaya River at Berwick.”

Those descriptions are at odds with the maps mentioned above and the United States Geological Survey website which says Bayou Teche “flows southeast to the Lower Atchafalaya River, 2 miles north of Patterson.”

When Bayou Vista began to be developed realtors began to market lots along the water as being on the Bayou Teche, Felterman said. That was the beginning of “the wrong name” being applied to the Lower Atchafalaya River, he said.

Patterson Mayor Rodney Grogan said all his life he knew the waterway as the Teche but has recently been educated on its proper name and makes a habit of calling it the Lower Atchafalaya River.

Felterman points to the now discontinued Patterson Rotary Club which changed its chapter name to the Lower Atchafalaya River in 2009 as an example of an organization that realized the correct name.

Others are not convinced the issue is important, including Berwick Mayor Louis Ratcliff.

“In recent decades, all the new houses on the waterfront have known it to be called Bayou Teche,” Ratcliff said. “It is all one body of water from the Calumet Cut to Berwick Bay.”

Felterman said he argued with the organizers of the Tour de Teche about calling the final miles of their race, now ending in Berwick, as the Bayou Teche, until they agreed he was right. The race originally ended in Patterson.

One of the original organizers of the paddling trip, Ken Grissom, said the group realizes that historically the Bayou Teche ends just north of Patterson.

“But, in practical terms we consider Bayou Teche as going to the Berwick locks,” Grissom said. Calling the event the Tour de Teche/Lower Atchafalaya River would be a bit cumbersome, he said.

Does it matter what name is used?

Longtime Patterson resident and businessman Frank Guarisco said the waterway should be called the correct name, Lower Atchafalaya River, because that is the name and it was never changed.

State Rep. Sam Jones, D-Franklin, diplomatically offered a Shakespeare quote.

“‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet,’” Jones said. “No matter what you call it, the waterway is a beautiful part of our heritage and culture and is a beautiful place.”

Felterman does not agree with his state representative.

“I don’t believe the Lower Atchafalaya River could smell as sweet if it is called the Teche,” Felterman insisted.

South Louisiana geology may make this issue moot in the future.

The American Wetlands Foundation described how the Mississippi River constantly shifts course. It said a crevasse about 2,000 years ago above Baton Rouge caused the Mississippi River to flow “through much of the present day Bayou Teche, eastward to a point bound on the north by present day Houma and on the south by the Gulf. This … was the active delta for 500 years.”

Richard Keim, an LSU assistant professor and hydrologist, said when the river switched to its present course, it left behind the Bayou Black and Teche ridges that extended into Terrebonne Parish. He said later, another crevasse break eventually became the Atchafalaya River; it was just a trickle of a river in the 1600s. That river broke over the Teche Ridge and crossed the Bayou Teche and swallowed up parts of associated water bodies, he said.

The Mississippi River changes course about every 1,000 years and it is overdue for its next course change, Keim said.

Keim said geologists agree that at some point, despite the best efforts of the corps, the Mississippi River will likely break through the Old River Control Structure built in 1964 and shift to flowing through the Atchafalaya channel.

- Log in to post comments