Elward and Olive Stephens of Stephensville met at a dance in Morgan City in 1947. They married and raised three sons.

(Submitted Photo Courtesy of Linda Cooke)

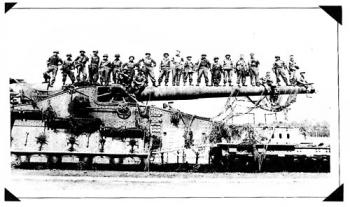

U.S. soldiers are shown on top of a German railroad artillery piece in Italy. Photo courtesy of World War II veteran Elward Stephens of Stephensville.

Stephensville veteran remembers WWII invasion, fighting in Italy

In September 1943, when World War II was well under way, the Germans under the command of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring were in control of the Italian Peninsula. Allied forces there had been unable to advance north of what the Germans called the Gustav Line.

Because American forces under General George Marshall did not seem receptive to plans to break the stalemate, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill appealed to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt. A plan was developed with a goal of attacking the Germans both north and south of this Gustav Line and from there advance to Rome. If the Germans in Italy could be defeated, they would not be able to join the Axis troops in Europe.

Anzio Beach, some 30 miles south of Rome, was chosen as the site of the invasion plan which was code-named Operation Shingle. On Jan. 24, 1944, the Allies landed on the beaches of Anzio — 36,000 men, 3,200 vehicles — encountering little resistance from the, as yet, unsuspecting Germans.

British General Alexander expected the troops to head quickly into the interior of Italy toward the Gustav Line, but apparently did not convey that desire forcefully to U.S. Generals Clark, Lucas and Truscott who felt they did not have sufficient troops and materials and felt no urgency to advance immediately.

Kesselring, now aware of the invasion and aware of the hesitancy of the Allied troops, took advantage of the delay to accumulate more troops and equipment. By Feb. 2, Kesselring had 70,000 troops ready and every Allied movement was met with fierce fighting and little success.

It was into this situation that Elward Stephens of Stephensville was delivered into.

Born on a camp boat in Belle River on Aug. 9, 1924, Stephens was one of five boys and one girl born to Gilbert and Alvina Chaisson Stephens. Elward Stephens went to a small, one-room school on what is now E. Stephensville Road.

Like most of the rural Louisiana schools in those days, public education went only as far as the sixth grade. Stephens remembers that the teacher would live with his student’s parents. Since there was no road at that time, the students walked to school or came by boat.

When Stephens was 15 years old, he rode a bicycle to his job in a Morgan City garage where he pumped gas at 10 cents a gallon. When he was 18, Stephens was drafted and sent to Fort McClellan, Ala., for basic training. In late 1943, he was shipped to Anzio, Italy, to take part in the Allied invasion of Italy.

“Conditions in Italy were bad,” Stephens said. “I fought for 230 straight days in the front lines. My feet suffered from frostbite. We got trench foot, and suffered from exposure. My feet still give me trouble today. I was nearly buried alive in my foxhole on several occasions. In the first five days, five men shot themselves in the foot in order to be sent home,” Stephens recalls.

Stephens is severely deaf today from the artillery bombardment he endured. Having some skill with weapons, Stephens carried a 30-pound Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) and was always accompanied by an ammunition carrier.

“One of the guys who was carrying my shells was shot right in the middle of his forehead,” Stephens remembered. “He died in my arms.”

“The fighting was so constant we couldn’t even take any kind of bath for months. For a long time we had to drink water from a small stream. Later we found that there were dead, decaying German bodies in the river just a way upstream from where we were drinking. Our skin developed blisters from sweat and dirt.”

The fighting was often hand-to-hand combat. A huge German gun known as Anzio Annie fired shells constantly into the Allied entrenchments from as far away as 20 miles.

“There was no time for much rest. We would sleep for one hour and be on guard duty for an hour,” Stephens said.

Casualties were so high there was little chance for any relief. Replacements of men and material were scarce.

“We had (K-rations) cheese for breakfast, pork loaf for lunch and ham for supper,” recalled Stephens. “And with each meal we got three cigarettes. I didn’t smoke before I was in the Army but I did then. My hands got black with cigarette smoke because we had to cup our hands around the cigarette to keep the red ash from showing. When I came home I was smoking three packs a day.”

Stephens said he was able to break his smoking habit because his wife, Olive, made such good fried chicken, a good substitute.

Eventually, the Allies managed to push the Germans back north, but due to some delays caused by more miscommunication among the Allied commanders, Kesselring’s troops were able to escape north. At the end of four months of sustained fighting, the allies suffered about 7,000 killed and 36,000 wounded or missing. German losses were around 5,000 dead, 30,500 wounded or missing and 4,500 captured.

On June 4 or 5, the Allied forces occupied Rome.

“Rome hadn’t been damaged much,” Stephens said. “Since I’m Catholic, I went to church there. It helped that I could speak French.”

Stephens traveled further to Pisa where he was given amphibious training and was shipped to Marseille, France. Fighting was not so intense there, but still bad. From there he walked almost to the German border. At this point, after 230 days of fighting, Stephens said he couldn’t go anymore. He and others were sent to a hospital in England where they rested until discharged and sent back to the states sometime in 1945 or maybe 1946.

Back in Stephensville, Stephens took an electronic course and went to work for Humble Oil (now Exxon Mobil). He worked on a quarter boat for Humble and participated in some exploratory seismographic work that discovered the first oil well in the Gulf of Mexico.

At a dance in Morgan City in 1947, Stephens maneuvered an introduction to an attractive young woman named Olive Boudreaux. They were married and have raised three sons. The Stephens live in a house built by Stephens himself. It is filled with mementos of the family — photos of children and grandchildren, and carved objects.

A few years ago the structure was raised to avoid the flooding common to the area. He learned to play the guitar via correspondence courses and learned to make a very tasty wine.

Stephens is now 89 years old. War-time dates are a bit vague but his memories are clear of those days.

Operation Shingle has been criticized for poor planning and poor execution. The Germans who escaped, rather than being captured, were able to join the forces in Europe.

Churchill, however, defended the Anzio Operation and said the invasion kept many Germans from being deployed to the European theater where they would have opposed the Normandy landings.

- Log in to post comments