Salute to veterans

George Beaugh is a 91-year-old retired shoe store owner, but seven decades ago he had one of the most dangerous jobs in the world.

Beaugh was a crewman on a B-17 Flying Fortress in the 8th Army Air Force tasked with attacking Nazi Germany.

Despite the years, Beaugh has little trouble remembering the other nine crewmembers and the missions they flew together into jaws of fierce German defenses.

From the nose and about 74 feet back to the tail, Beaugh rattled off the names of the crew, which eventually would become one of the most decorated in World War II.

Beaugh was a flight engineer and manned the top turret gun, one of eight gun positions on the four-engine bomber.

“J.B. Brooks from New Orleans was bombardier,” Beaugh said. “Navigator was Vincent Fazio from Massachusetts. He was first generation. His parents came from Italy.”

Beaugh continued through to “tail gunner was William and we called him ‘Cotton picking Willie.’ Willie Williamson. He was from a little town in Arkansas not far from the Texas line.”

Beaugh, who lives in Morgan City with his wife, Norma, raised five children here and owned and operated The Shoe House from 1956 to 1994.

Beaugh enlisted for the duration of the war in May 1942, just months after the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese attack on the U.S. fleet in Pearl Harbor that plunged the nation into a war that wouldn’t end until August 1945.

The Lewisburg native said, “They had a big drive in Opelousas one day recruiting for the Army Air Corps. I went and signed up. I wasn’t going to get drafted.”

Training followed from Camp Beauregard, California and Texas to Nebraska and, finally, in a brand new B-17. The crew flew with 43 other bombers to join the fight in Europe.

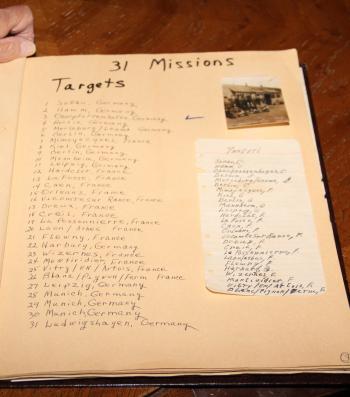

Beaugh eventually would complete 31 combat missions, which include an April 24, 1944, bombing run targeting a jet aircraft plant in Oberpfoffenhofen, Germany.

The mission cost the lives of two crewmembers and wounded five others.

The crews started at 2 a.m. from an airbase at Grafton-Underwood where the hundreds of airmen ate breakfast and were briefed.

What followed that day in April was a 10-hour trip into hell.

As the crew of Beaugh’s White Angel and other bombers approached the target, they were hit hard by Messerschmitt 109s, Beaugh said.

“My turret was out of commission,” he said. “A 20mm hit right in front of me and exploded when it hit armor plating. I came out of this without a scratch on me. I thought I was dead.”

In 1994, Beaugh told his story to Ron Delhomme of The Daily World in Opelousas.

“We were flying as many missions as they could put in the air to soften the Germans up for the invasion,” he said. “Our mission was to get that plant out. Twice we saw the jets, and they were fast. We couldn’t allow them to make a bunch of these things or they would have taken control of the air.”

The fighters were attacking from 12 o’clock high and raked Beaugh’s bomber.

The navigator was killed in one attack, a waist gunner was killed, the bombardier was wounded, and the German fighters kept attacking.

A 20mm shell exploded at the feet of the pilot, Lt. Charles F. Gowder, 28, burning his leg. Another shell destroyed the instrument panel.

Gowder held the plane steady to complete the bomb run and used an emergency release to drop the bombs.

The White Angel, which an Army public relations officer renamed the Liberty Run, still had to run through anti-aircraft fire.

After that was over there were more fighter attacks.

By that time there was only one machine gun station left.

Beaugh said Gowder dropped the plane from its bombing altitude of about 25,000 feet to about 15,000 feet and eventually flew a tree-top run back to England.

“A fighter will not attack you that close to the ground because he has to come at you at an angle,” Beaugh said.

Gowder was diving, climbing and kicking the plane around to evade the fighters, he said.

Four Allied fighters, two P-47s and two Spitfires flanked the bomber and guided them to an airbase in England.

“The brakes were out, tires flat and yet it stayed on the runway and came to a stop,” he said.

“You felt as though a miracle could happen. We can get back,” he said.

Crews were offered the Last Sacrament when they left, he said.

“Every time you went out somebody was not coming back,” he said.

Beaugh was never wounded, hospitalized or missed a mission.

The 31st and final combat flight for Beaugh was an 11-hour mission to Ludwigshagen, Germany and back on July 19, 1944.

There were 26,000 deaths out of 350,000 airmen in the 8th Army Air Force during World War II, according to the 8th Air Force Historical Society. By comparison there were 37,000 deaths out of 4.1 million sailors who served in World War II.

“There was no such thing as an atheist flying into combat,” Beaugh said.

Beaugh was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross twice, the Air Medal five times and several presidential commendations for his service in World War II.

- Log in to post comments